Why I did this

Heroku is great, but not in 100% of cases

When I want to quickly deploy a Rails application, my go-to choice is Heroku. I’m a big fan of the idea that I can just run heroku create and have a production application online in just a matter of seconds.

Unfortunately, Heroku isn’t always a desirable option. If I’m just messing around, I don’t usually want to pay for Heroku features, but I also don’t always want my dynos to fall asleep after 30 minutes like on the free tier. (I’m aware that there are ways around this but I don’t necessarily want to deal with the hassle of all that.)

Also, sometimes I want finer control than what Heroku provides. I want to be “closer to the metal” with the ability to directly manage my EC2 instances, RDS instances, and other AWS services. Sometimes I desire this for cost reasons. Sometimes I just want to learn what I think is the valuable developer skill of knowing how to manage AWS infrastructure.

Unfortunately, using AWS by itself isn’t very easy.

Setting up Rails on bare EC2 is a time-consuming and brain-consuming hassle

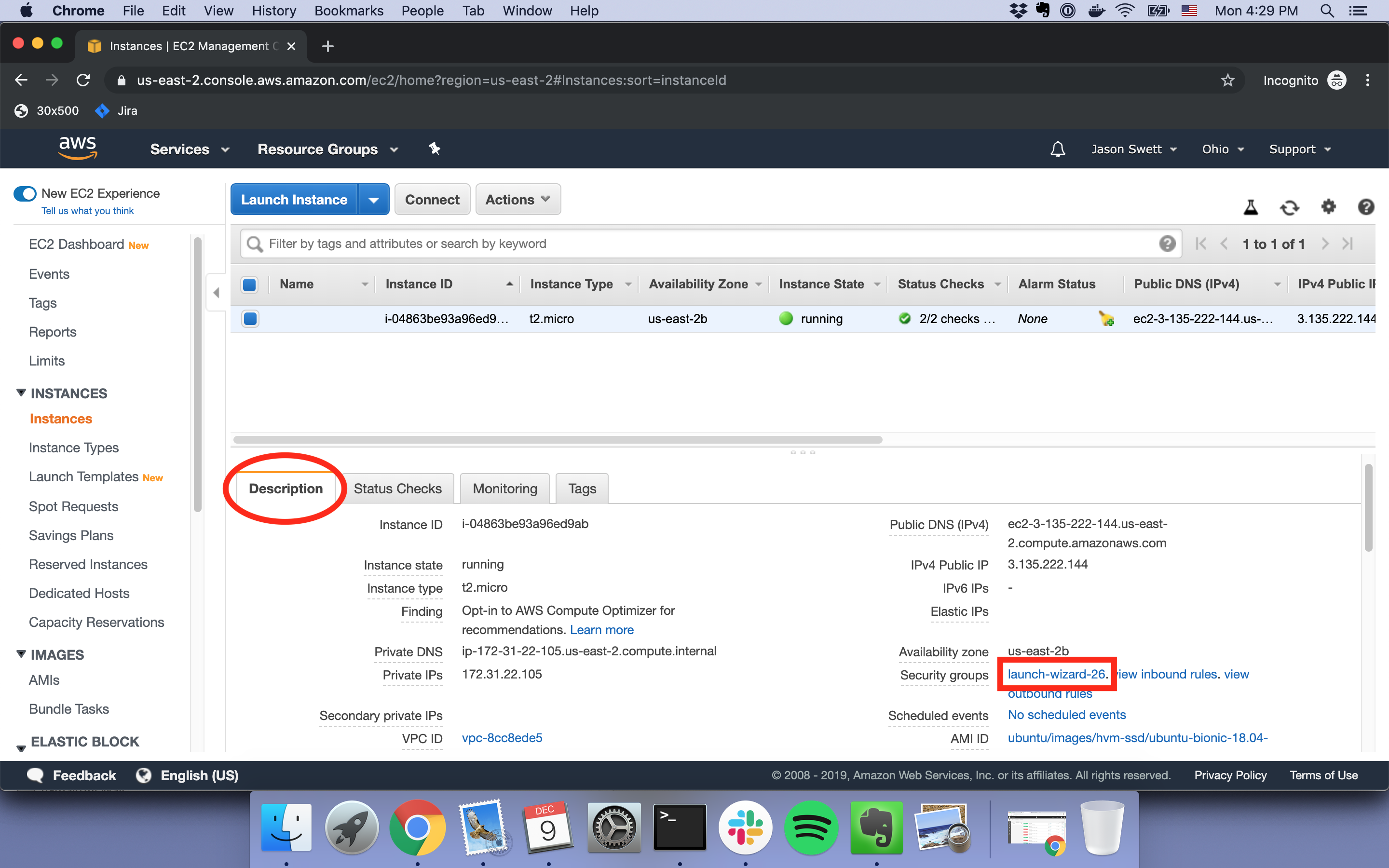

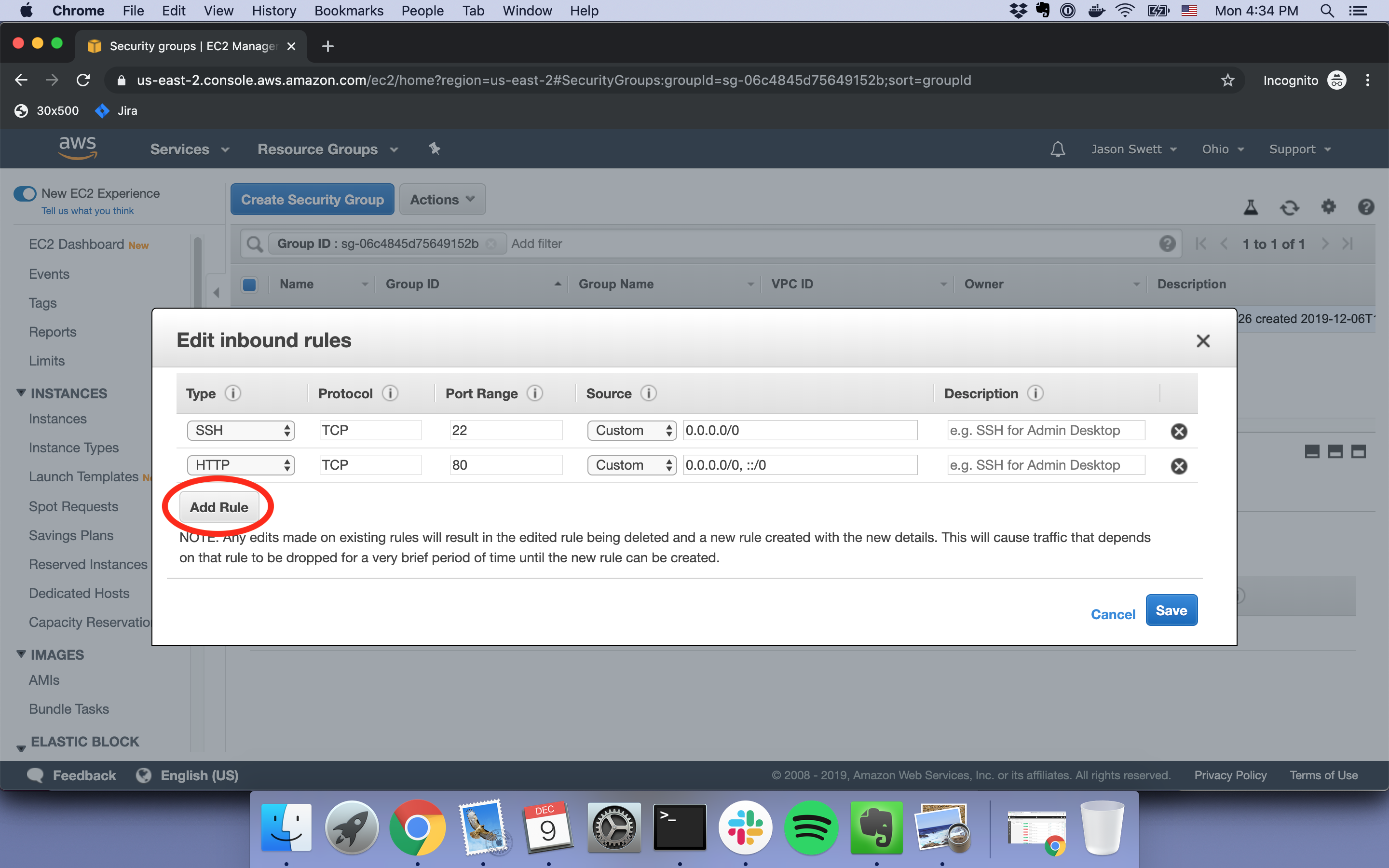

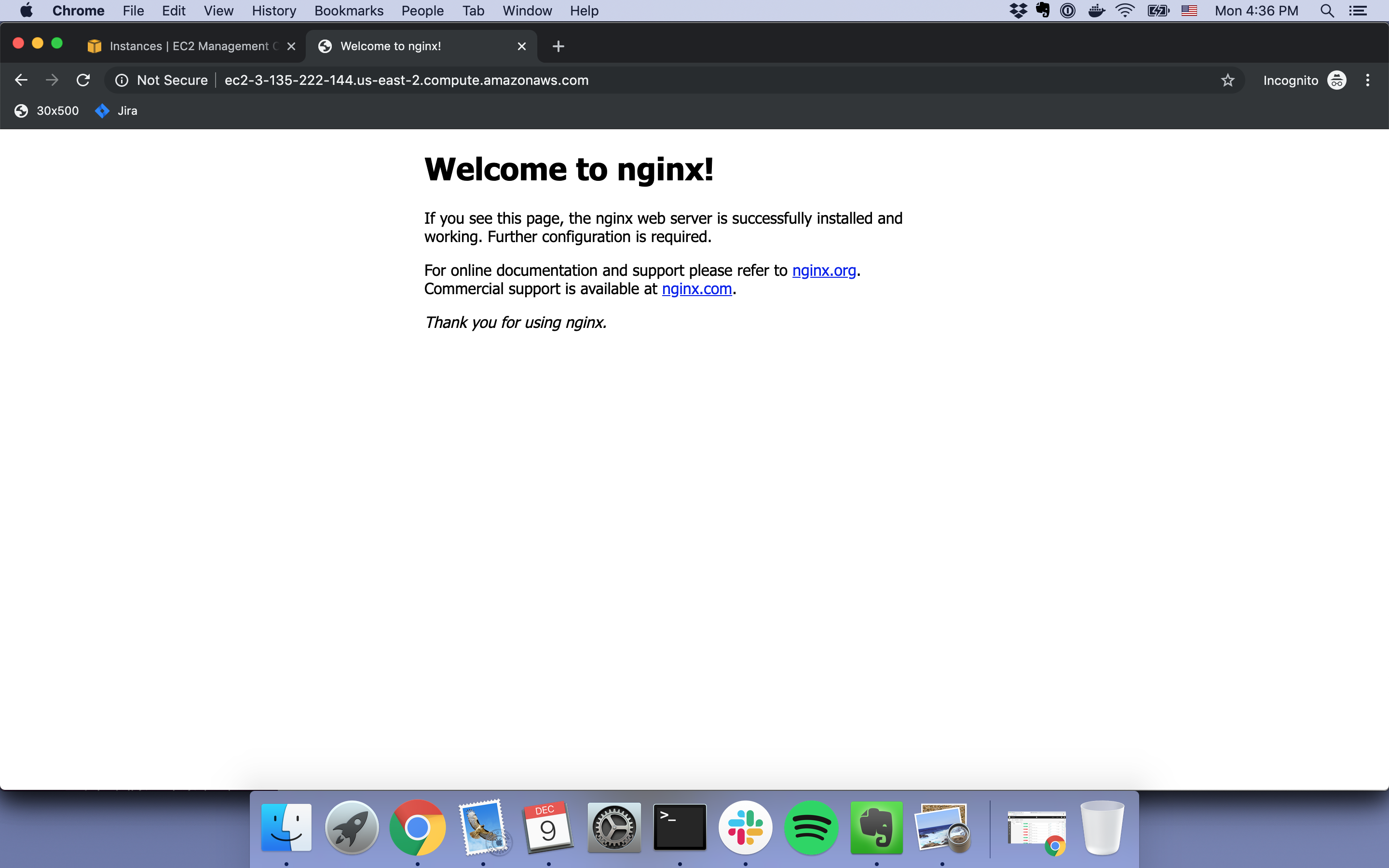

Getting a Rails app standing up on AWS is pretty hard and time-consuming. I’m actually not even going to get into Rails-related stuff in this post because even the small task of getting an EC2 instance up and running—without no additional software installed on that instance—is a lot harder than I think it should be, and there’s a lot to discuss and improve just inside that step.

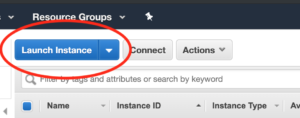

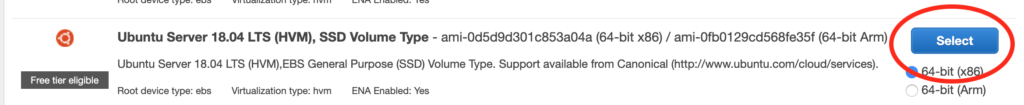

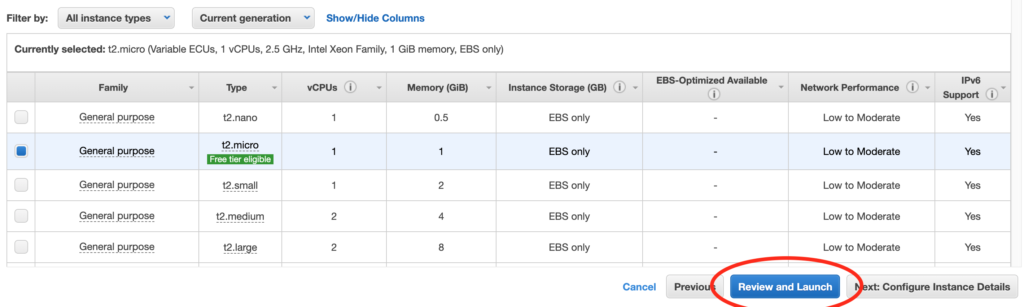

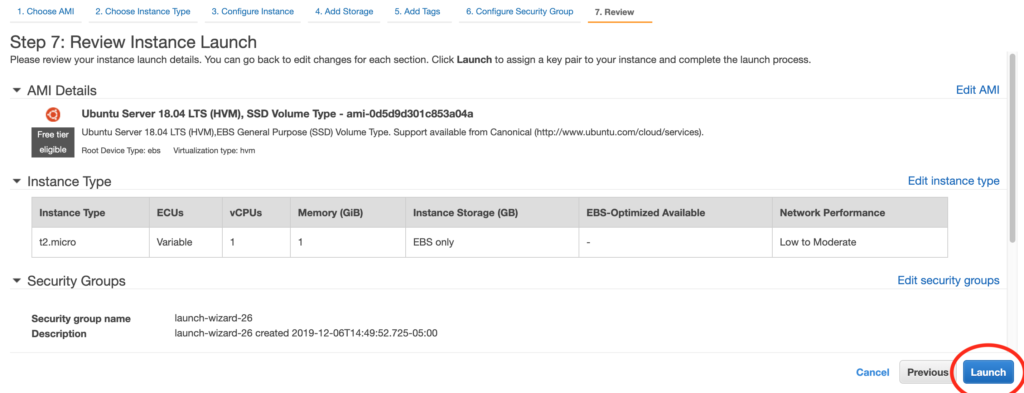

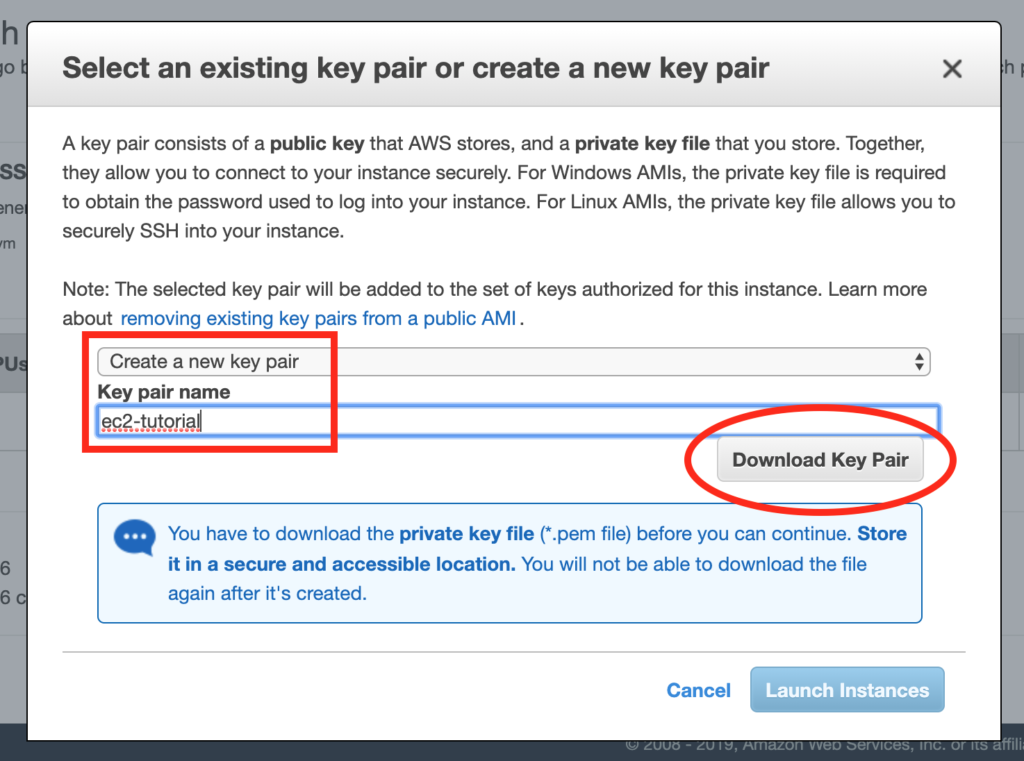

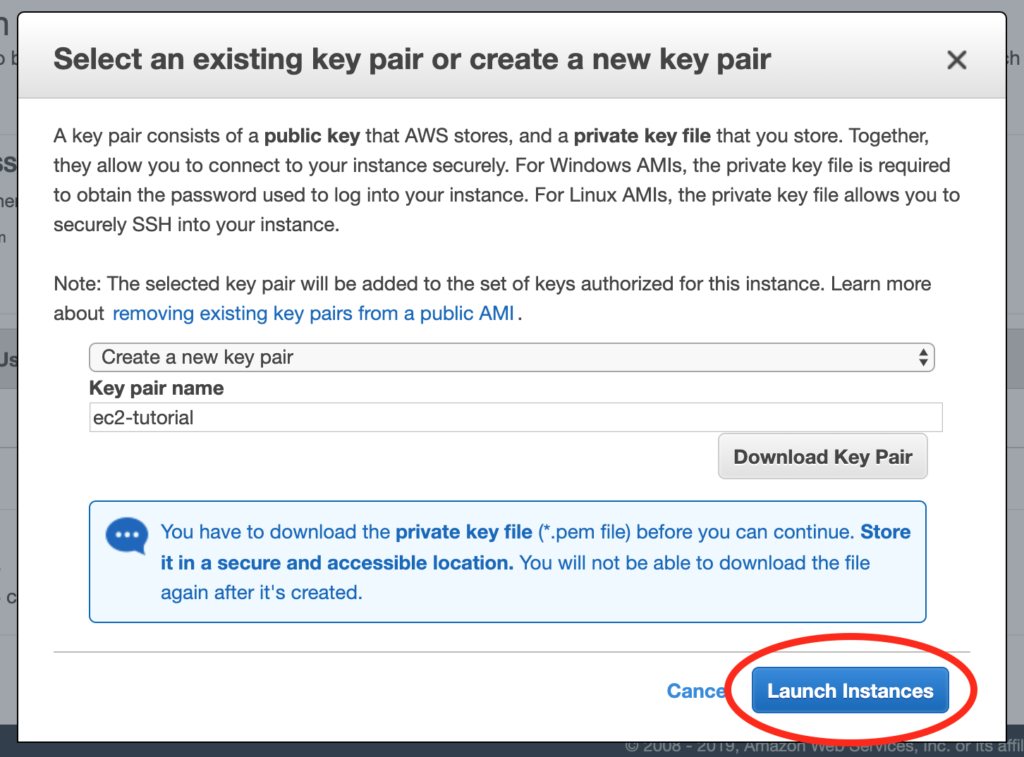

Just to briefly illustrate what a pain in the ass it is to get an EC2 instance launched and to SSH into it, here are the steps. The steps that follow are the command-line steps. I find the AWS GUI console steps roughly equally painful.

1. Use the AWS CLI create-key-pair command to create a key pair. This step is necessary for later when I want to SSH into my instance.

2. Think of a name for the key pair and save it somewhere. Thinking of a name might seem like a trivially small hurdle, but every tiny bit of mental friction adds up. I don’t want to have to think of a name, and I don’t want to have to think about where to put the file (even if that means just remembering that I want to put the key in ~/.ssh, which is the most likely case.

3. Use the run-instances command, using an AMI ID (AMI == Amazon Machine Image) and passing in my key name. Now I have to go look up the run-instances (because I sure as hell don’t remember it) and, look up my AMI ID, and remember what my key name is. (If you don’t know what an AMI ID is, that’s what determines whether the instance will be Ubuntu, Amazon Linux, Windows, etc.)

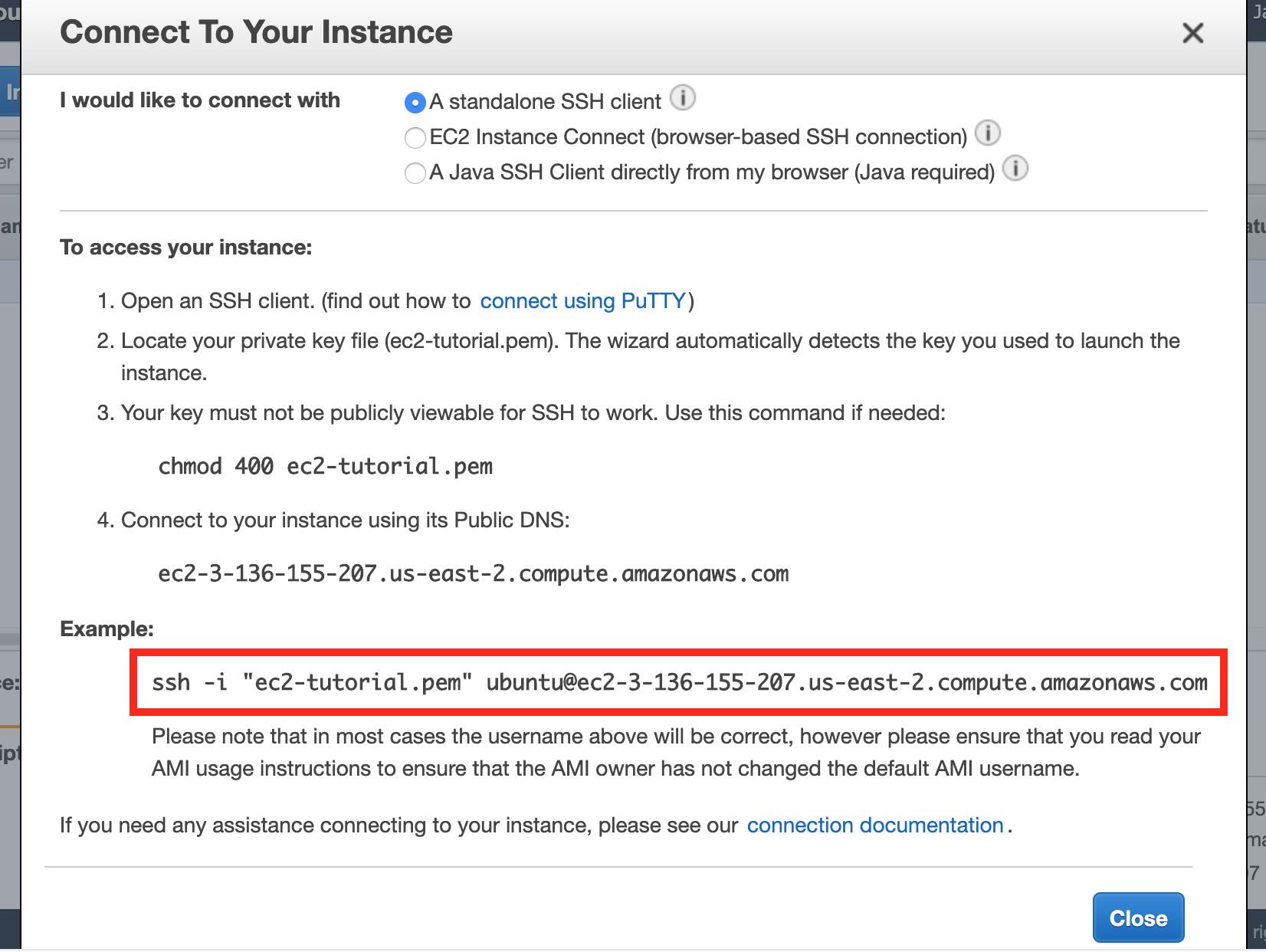

4. Use the describe-instances command to find out the public DNS name of the instance I just launched. This means I either have to search the JSON response of describe-instances for the PublicDnsName entry or apply a filter. Just like with every AWS CLI command, I’d have to go look up the exact syntax for this.

5. Run the ssh command, passing in my instance’s DNS and the path to my key. This step is probably the easiest, although it took me a long time to commit the exact ssh -i syntax to memory. For the record, the command is ssh -i ~/.ssh/my_key.pem ubuntu@mypublicdns.com. It’s a small pain in the ass to have to look up the public DNS for my instance again and remember whether my EC2 user is going to be ubuntu or ec2-user (it depends on what AMI I used).

My goals for my AWS command-line tool

All this fuckery was a big hassle so I decided to write my own command-line tool to manage EC2 instances. I call the tool Exosuit. You can actually try it out yourself by following these instructions.

There were four specific capabilities I wanted Exosuit to have.

Launch an instance

By running bin/exo launch, it should launch an EC2 instance for me. It should assume I want Ubuntu. It should let me know when the instance is ready, and what its instance ID and public DNS are.

SSH into an instance

I should be able to run bin/exo ssh, get prompted for which instance I want to SSH into, and then get SSH’d into that instance.

List all running instances

I should be able to run bin/exo instances to see all my running instances. It should show the instance ID and public DNS for each.

Terminate instances

I should be able to run bin/exo terminate which will show me all my instance IDs and allow me to select one or more of them for termination.

How I did it

Side note: when I first wrote this, I forgot that the AWS SDK for Ruby existed, so I reinvented some wheels. Whoops. After I wrote this I refactored the project to use AWS SDK instead of shell out to AWS CLI.

For brevity I’ll focus on the bin/exo launch command.

Using the AW CLI run-instances command

The AWS CLI command for launching an instance looks like this:

aws ec2 run-instances \

--count 1 \

--image-id ami-05c1fa8df71875112 \

--instance-type t2.micro \

--key-name normal-quiet-carrot \

--profile personal

Hopefully most of these flags are self-explanatory. You might wonder where the key name of normal-quiet-carrot came from. When the bin/exo launch command is run, Exosuit asks “Is there a file defined at .exosuit/config.yml that contains a key pair name and path? If not, create that file, create a new key pair with a random phrase for a name, and save the name and path to that file.”

Here’s what my .exosuit/config.yml looks like:

---

aws_profile_name: personal

key_pair:

name: normal-quiet-carrot

path: "~/.ssh/normal-quiet-carrot.pem"

The aws_profile_name is something that I imagine most users aren’t likely to need. I personally happen to have multiple AWS accounts, so it’s necessary for me to send a --profile flag when using AWS CLI commands so AWS knows which account of mine to use. If a profile isn’t specified in .exosuit/config.yml, Exosuit will just leave the --profile flag off and everything will still work fine.

Abstracting the run-instances command

Once I had coded Exosuit to construct a few different AWS CLI commands (e.g. run-instances, terminate-instances), I noticed that things were getting a little repetitive. Most troubling, I had to always remember to include the --profile flag (just as I would if I were typing all this on the command line manually), and I didn’t always remember to do so. In those cases my command would get sent to the wrong account. That’s bad.

So I created an abstraction called AWSCommand. Here’s what a usage of it looks like:

command = AWSCommand.new(

:run_instances,

count: 1,

image_id: IMAGE_ID,

instance_type: INSTANCE_TYPE,

key_name: key_pair.name

)

JSON.parse(command.run)

You can probably see the resemblance it bears to the bare run-instances usage. Note the conspicuous absence of the profile flag, which is now automatically included every single time.

Listening for launch success

One of my least favorite things about manually launching EC2 instances is having to check periodically to see when they’ve started running. So I wanted Exosuit to tell me when my EC2 instance was running.

I achieved this by writing a loop that hits AWS once per second, checking the state of my new instance each time.

module Exosuit

def self.launch_instance

response = Instance.launch(self.key_pair)

instance_id = response['Instances'][0]['InstanceId']

print "Launching instance #{instance_id}..."

while true

sleep(1)

print '.'

instance = Instance.find(instance_id)

if instance && instance.running?

puts

break

end

end

puts 'Instance is now running'

puts "Public DNS: #{instance.public_dns_name}"

end

end

You might wonder what Instance.find and instance.running? do.

The Instance.find method will run the aws ec2 describe-instances command, parse the JSON response, then grab the relevant JSON data for whatever instance_id I passed to it. The return value is an instance of the Instance class.

When an instance of Instance is instantiated, an instance variable gets set (pardon all the “instances”) with all the JSON data for that instance that was returned by the AWS CLI. The instance.running? method simply looks at that JSON data (which has since been converted to a Ruby hash) and checks to see what the value of ['State']['Name'] is.

Here’s an abbreviated version of the Instance class for reference.

module Exosuit

class Instance

def initialize(info)

@info = info

end

def state

@info['State']['Name']

end

def running?

state == 'running'

end

end

end

(By the way, all the Exosuit code is available on GitHub if you’d like to take a look.)

Success notification

As you can see from the code a couple snippets above, Exosuit lets me know once my instances has entered a running state. At this point I can run bin/exo ssh, bin/exo instances or bin/exo terminate to mess with my instance(s) as I please.

Demo video

Here’s a small sample of Exosuit in action:

Try it out yourself

If you’d like to try out Exosuit, just visit the Getting Started with Exosuit guide.

If you think this idea is cool and useful, please let me know by opening a GitHub issue for a feature you’d like to see, or tweeting at me, or simply starring the project on GitHub so I can gage interest.

I hope you enjoyed this explanation and I look forward to sharing the next steps I take with this project.